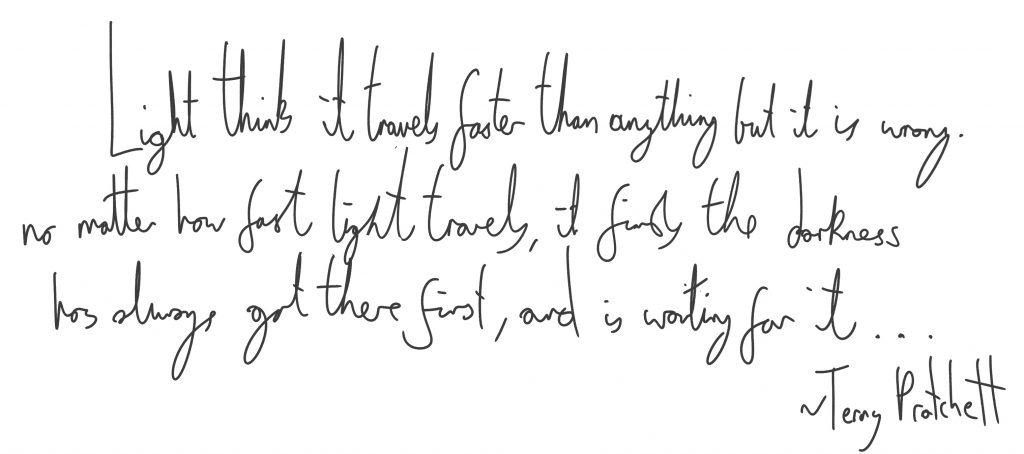

The D̘̜͔̫̹̬̖̍͂a͈̰̮̫̼͕̮ͣ̔̇͒͛̎̚͢r͂͑̒̽k̴̘͉̠̭͚͚ͤͫ̽ͪ Shepherd

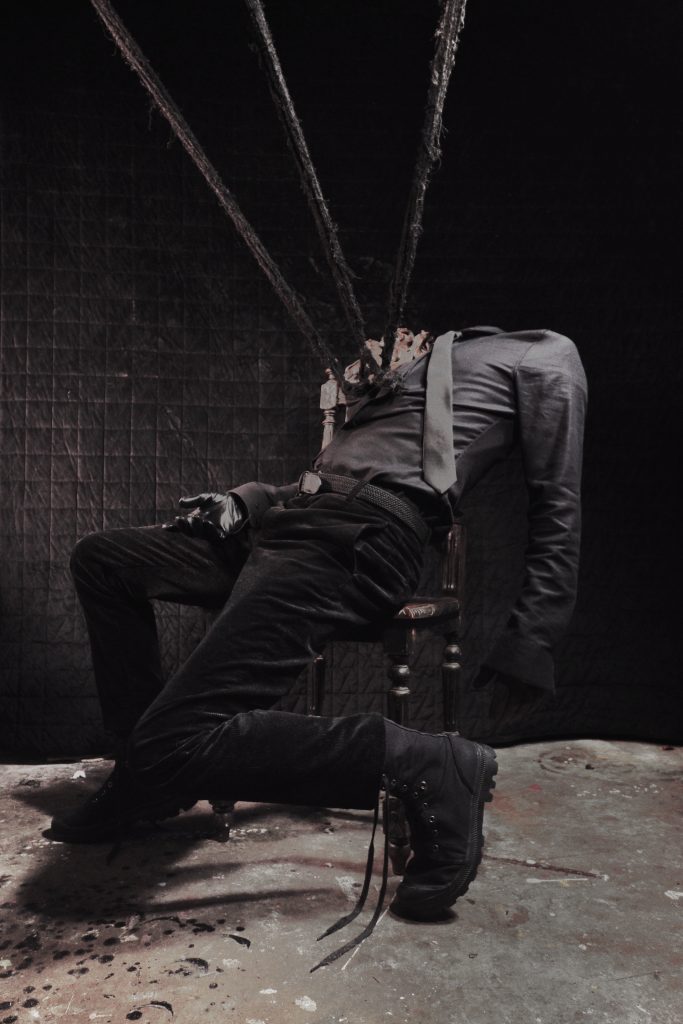

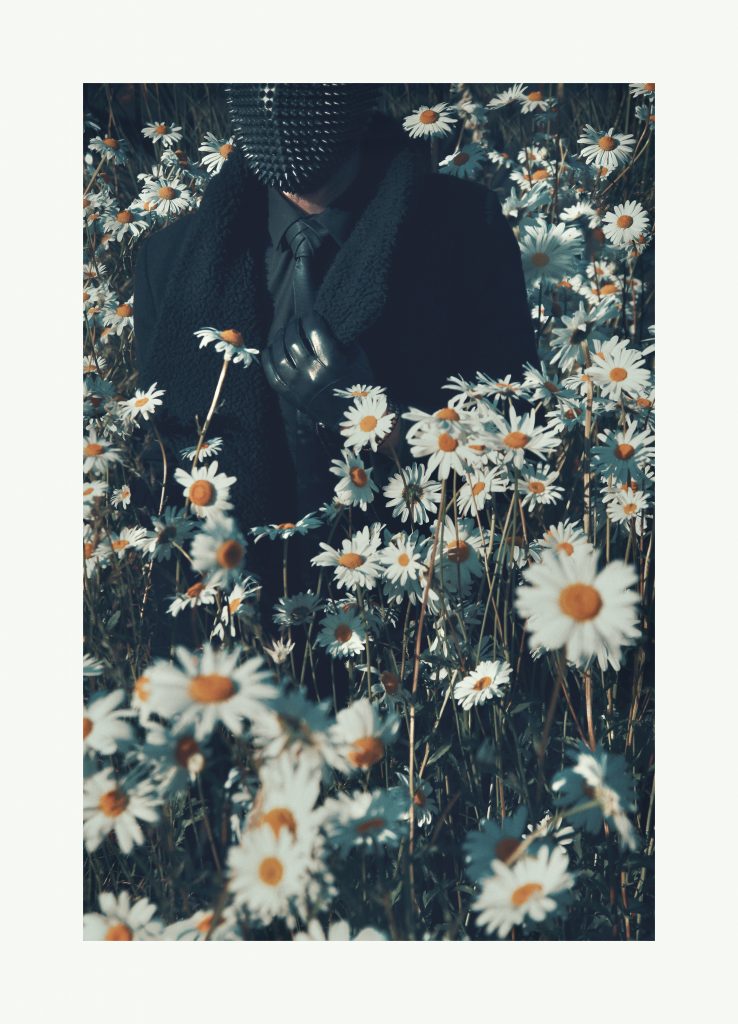

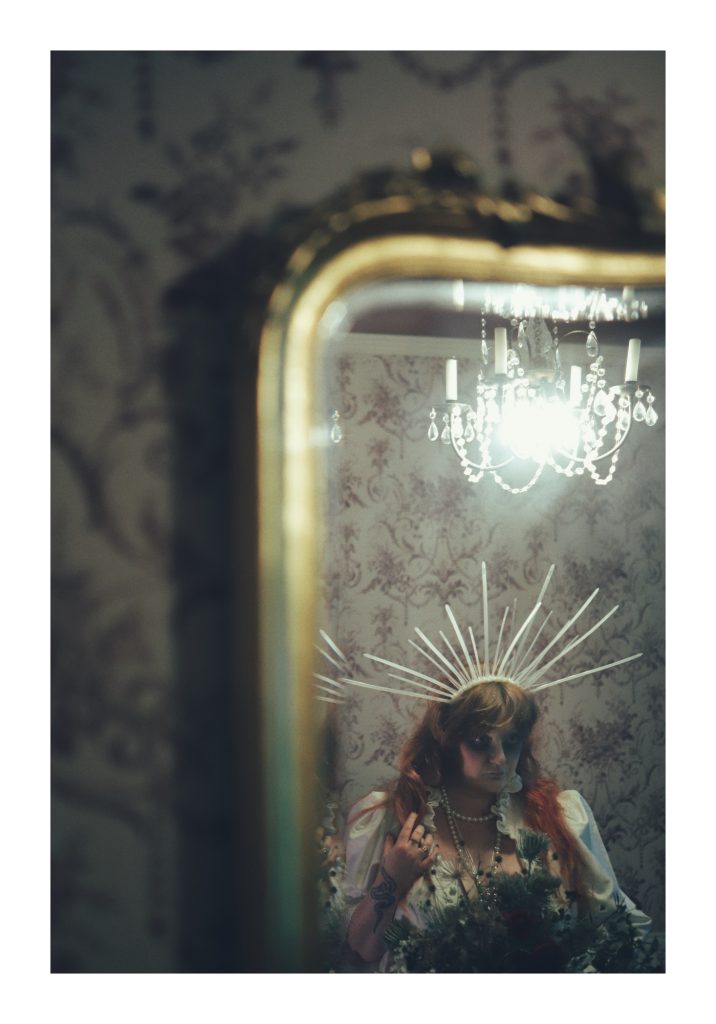

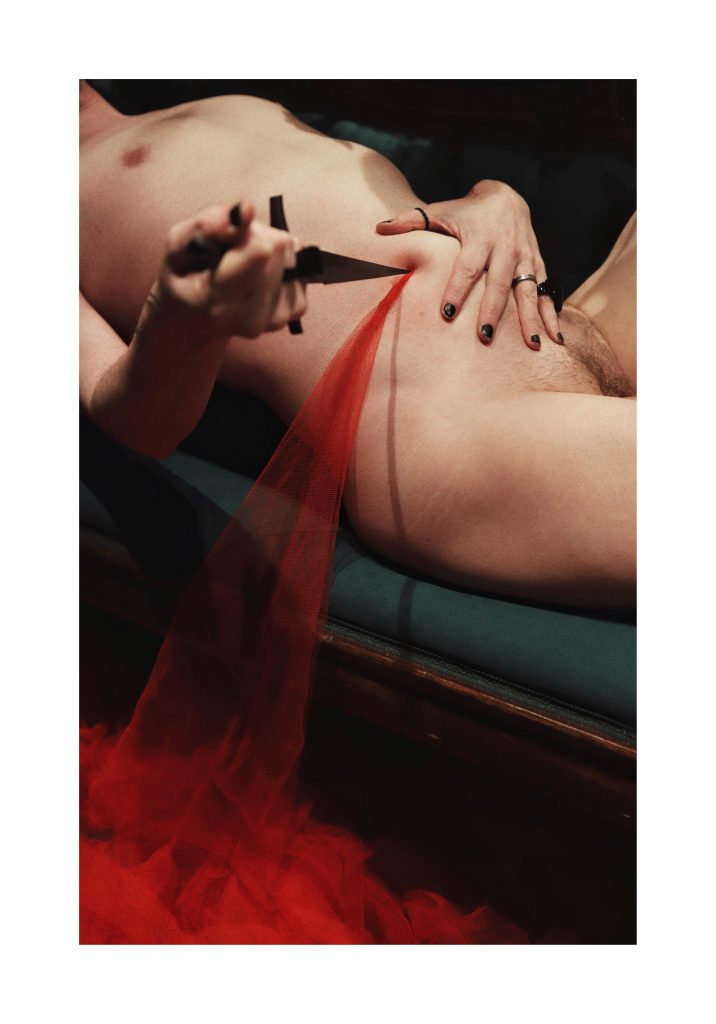

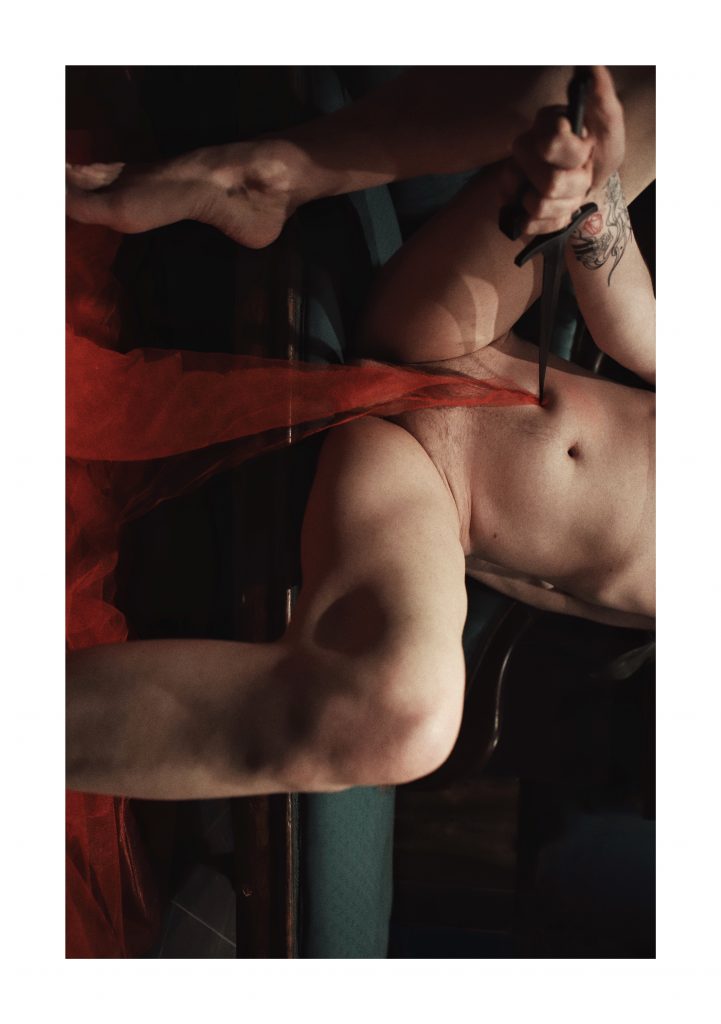

{i}

When moral argument falls on deaf ears, a Good Shepherd might have a Đ₳Ɽ₭ Shepherd moment, herding the sheep along the path of righteousness with the stabby end of the crook.

If an evil-doer has been remonstrated in some morally sound way, once they’re around the corner, safe and alone, they may suffer doubt… or perhaps they were only acting remorseful to escape, with no intention of repentance.

Whether out of habit or malice, the evil-doer is poised to forget the moral lesson and do the exact same thing that got them in trouble. At which point, the D̶̳̩̍̾a̸̗̤͎͐͂̚͝ŕ̵̛̩͐k̶͉̻̟̺̾̂̑͠ Shepherd steps in. >

The Devil’s got my ear today, I’ll never hear a word you say..}}}

█▄─▄▄▀██▀▄─██▄─ The Good Shepherd is optimistic in his heavenly intentions and arguments, but the DͩAͣRͬᴋⷦ Shepherd focuses on the evil in people.

The Dark Shepherd resorts to threats and fear in the sheep’s moment of doubt or descent, to scare the sheep away from the edge of the cliff. The 𝐃⃥⃒̸𝐚⃥⃒̸𝐫⃥⃒̸𝐤⃥⃒̸ Shepherd <i>/.can</i> be evil. His point is that you shouldn’t be.

While his Good Counterpart has integrity, the D̬͈̭A̴͚̯̙R̴̼̹̜̙̫K͇̟̺̺͚̫͈ Shepherd has low expectations. Out of sympathy or disgust, he sees the sheep as egocentric, thoughtlessly driven by pleasure or pain, incapable of learning, or perhaps just too addicted to bad behavior, too weak to make the right decision.

If the sheep won’t do the right things for the right reasons, the D̷̶͍̟̠̿̾̑̊͂ͬ͐͘͞͠ͅẢ̷ͪ͊ͩͬ̐ͮ҉̶̢̯͓̤̩͈̪̝͔̦̫͓͙́ͅR̶̉ͣ̎̉ͨ̄̈́̌̏ͪ͏̭͍͚̝͍̫͓͍̗͍̜̠̜͉̙̪̣̼K̸̨̦̦̲͉͔̭̙̠͙͖͓͚͖̟̳͇̾͋ͭ̑̆̓̋̓̈̃̄͘ͅ Shepherd encourages an alternative.

./ A Đⱥɍҟ Shepherd moment can become a lasting transformation when a good person is made weak by a lapse of faith, resorting to evil methods {intimidation, insult, injury} to achieve an end.

The underlying assumption can be dark: Good deeds aren’t intrinsically satisfying enough.

However, the D̬͈̭A̴͚̯̙R̴̼̹̜̙̫K͇̟̺̺͚̫͈ Shepherd may remain good and faithful if the motivation behind his action is merciful: Good is hard to understand and choose at first, so in the meantime…

Heaven is the carrot; Hell is the stick; the D̷̸̨͉͎͙̦̜͕̅ͤ̈́́̾̑̈́̒A̷̲̖̖̯̪̯͖̭͈̺̱̤̟̤̯̼̮̱̯ͯ͐͊ͦ̂́͗̿̽ͯͣ̒́̚͜R͔͈̗̺̳͙̜̖̥̪͇͉̊̂́̈ͪ̌́͌́̌̋̀K̶̢͈̮͓̱̥̤̺ͬͮ̌̒͛̒͗̏̽͟͜ shepherd wields the latter.

if you haven’t got a seat at the table then you’re probably on the menu…

The Persistence of Loss {i} {the cell that holds me, breaks me}

The Persistence of Loss {iii} {I count the days to find what was left behind}

Domestic Demi-God

absolutes sting as a duellist's glove.

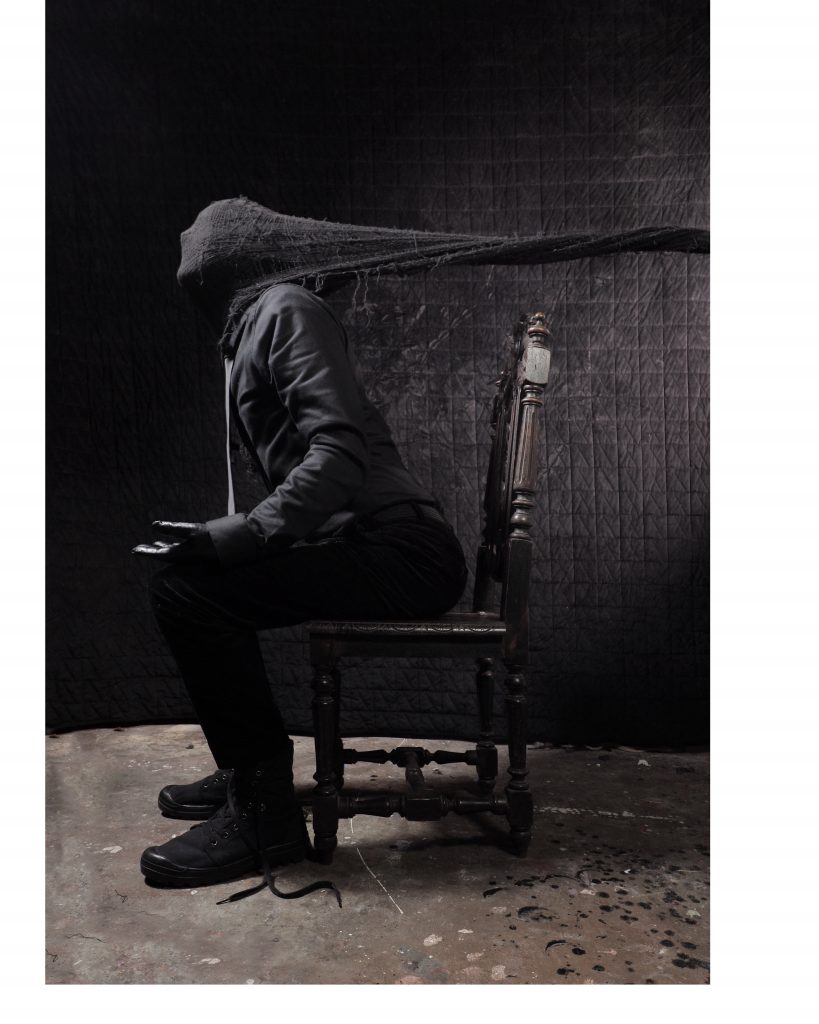

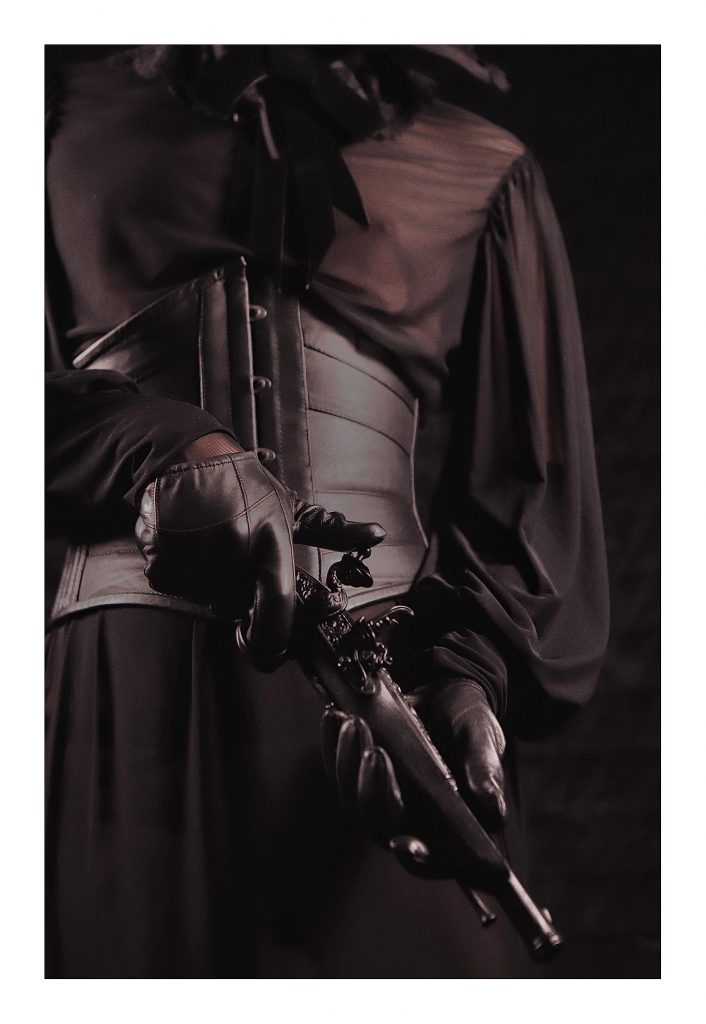

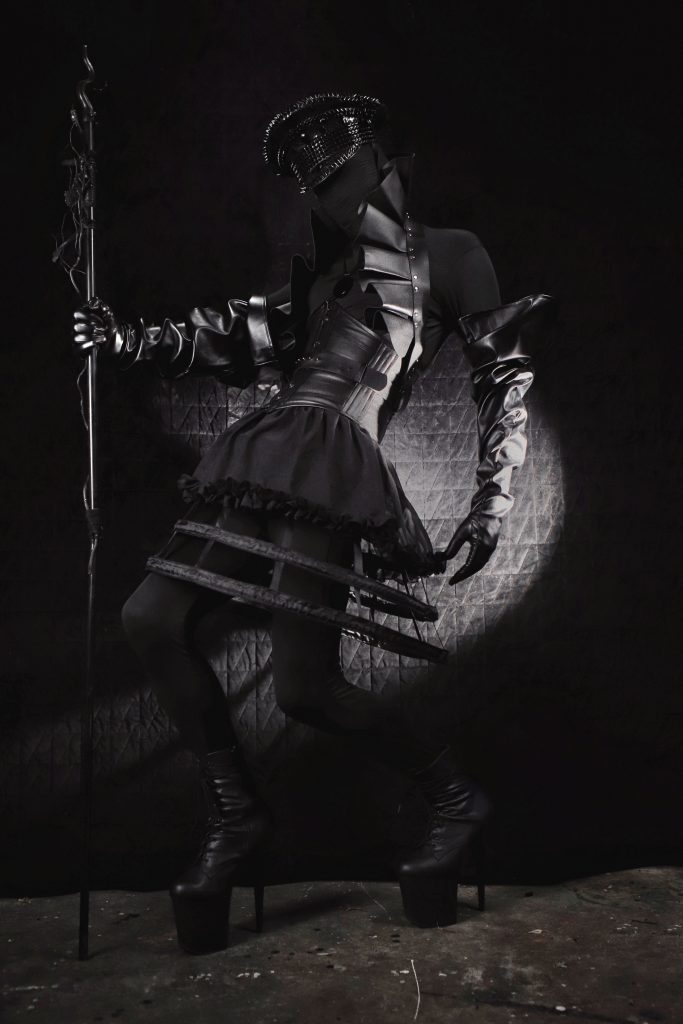

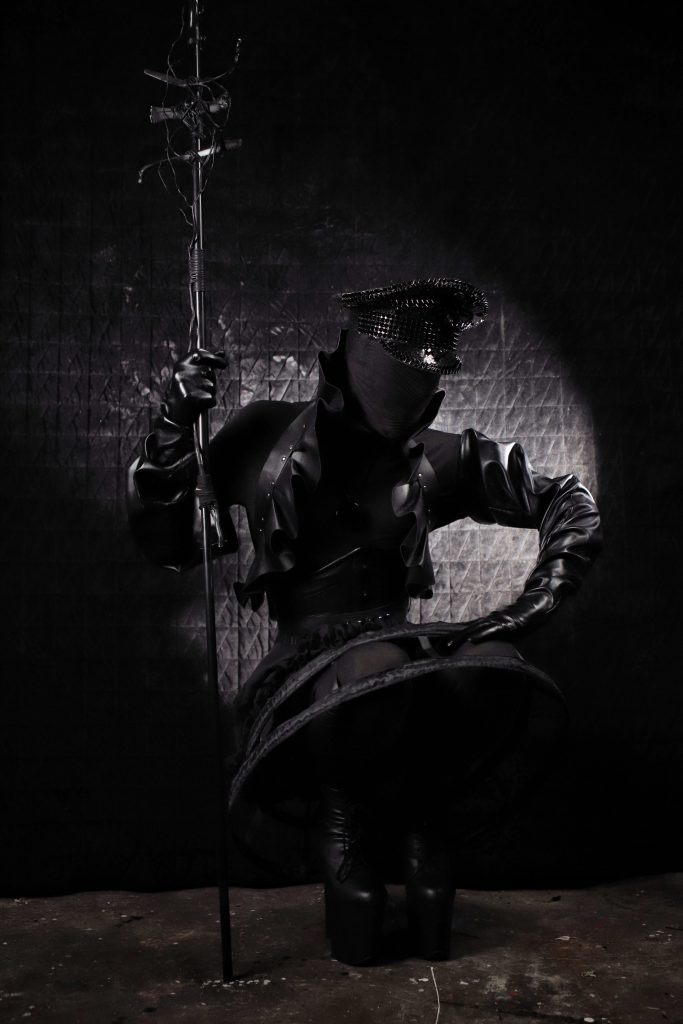

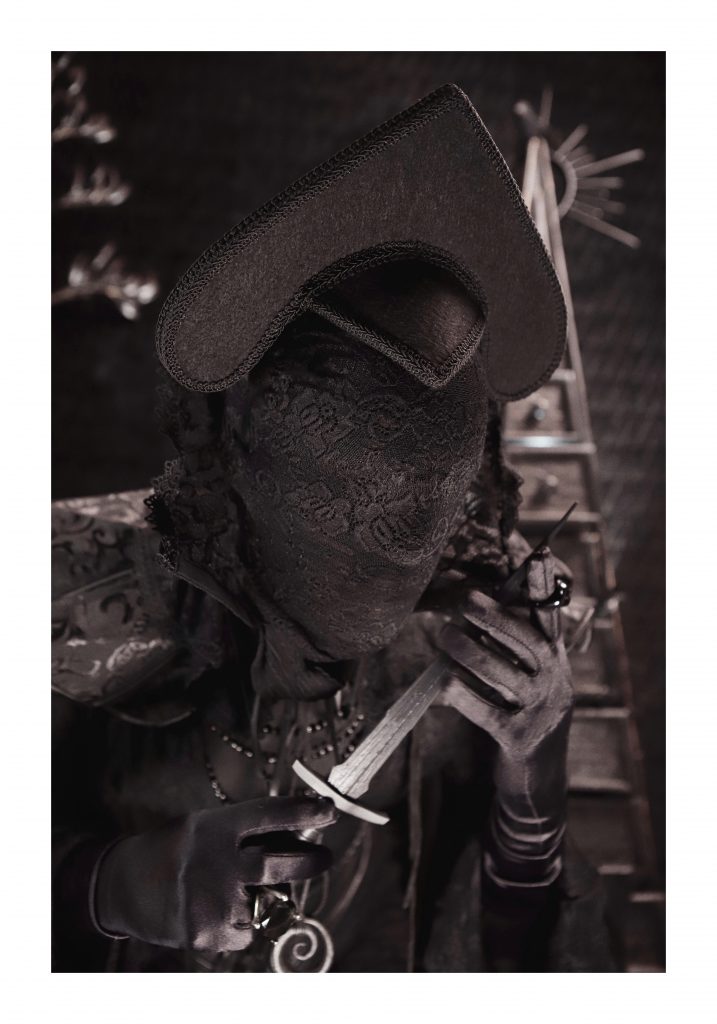

THE FUNERAL MUTE

During the Regency, as had been the case for over two centuries, most upscale funerals were comprised of a number of attendants, including “mutes.” Like the majority of funeral attendants at this time, these mutes were provided by the undertaker as part of their services. Though most of these “mutes” were perfectly capable of speech, it was their responsibility, not only to remain silent throughout the duration of every funeral, but also to maintain an exaggeratedly mournful expression while they served in the capacity of mute. Macabre as it may seem, during the Regency, there were men and boys who regularly supplemented their income as professional mutes.

Funeral mutes during the Regency . . .

The earliest concept of the funeral mute can be dated back to Ancient Rome. It was the custom for a mime to walk in the funeral procession of a deceased member of an important family. The Roman mime dressed all in black and wore a mask made of wax which was fashioned to look like the departed. Each mime was chosen based on their physical resemblance to the person who had passed away. As he walked in the procession, the mime did his best to mimic the mannerisms of the deceased and his family. This masked mime was intended to represent the physical personification of the ancestors of the newly departed, come to earth in order to provide their relative with an escort into the underworld.

About 1600, the mute had become a required attendant at the funerals of the English upper classes. Like the Roman funeral mime, they dressed all in black and walked in the funeral procession. At about this same time, it became customary to have two mutes rather than just one. But unlike the Roman mime, mutes did not mimic the deceased person, but walked solemnly behind the feathermen, who typically led the procession. Nevertheless, by the turn of the eighteenth century, similar to the Roman funeral mime, the mute was considered to be the symbolic protector of the newly departed person. A pair of mutes would stand near the door of the home of the deceased while the body lay within. The mutes would then walk in the funeral procession when the body was taken to the church. Once the coffin was carried into the church, the mutes would take up their position at the door of the church during the funeral service. Though there are few records from this period, it appears that mutes were hired directly by the family of the departed, or might even have been servants of that family.

With the rise of the professional undertaker at the end of the eighteenth century, the undertaker took on the responsibility of hiring all of the attendants for a funeral, including the mutes. The undertaker also had the implied responsibility for safe-keeping of the body until the burial. Many mutes deputized for the undertaker, who was often managing more than one funeral at a time. As had mutes in previous decades, two mutes would take up their position on either side of the door of the departed’s home while the family kept vigil around the body. Mutes often helped to place the coffin in the hearse, then walked in the funeral procession when the deceased was taken to the church. There, they took up their places outside the doors of the church during the funeral service. Often mutes accompanied the coffin to the graveside, standing back during that final service. Once the mourners departed, the mutes often helped to fill in the grave as part of their duties.

In accordance with tradition, funeral mutes typically wore a white shirt, black suit, black shoes, black gloves, and a large black sash across their torso. They also wore a black beaver hat, swathed with crepe with a narrow length which trailed down their back. For most funerals, the mute’s hat was swathed with black crepe, unless the funeral was for a child or an unmarried person. In those cases, the mute’s hat was wrapped with white crepe and the mute wore a white sash and white gloves. Mutes also carried tall staffs which were believed to harken back to the staves of the castle porters who stood watch during ancient baronial funerals. These staffs had a cross-piece affixed near the top from which a length of crepe was hung. The crepe was secured with a large bow near the middle of the staff. The crepe which was draped over the mute’s staff was usually black, again, with the exception of funerals for children or unmarried people, when the staff was draped in white crepe.

There appear to have been two rather distinct classes of mutes. The more prominent undertakers who served the better classes hired professional mutes who also stood as their representatives to their clients for the duration of the preparation for the funeral, the funeral procession, service and burial. In quite a number of cases, these professional mutes came from a family whose male members spent their working lives as funeral mutes. Their wives, sisters and daughters may also have found work in the funeral industry preparing bodies for burial, a task usually assigned to women. However, there was another, less savory class of men who worked as mutes for less prominent and less affluent undertakers. These men often did not have steady jobs and took whatever work they could get. There were some advantages to working as a mute. In some cases, they would be provided with a full suit of clothes.

At the very least, they would be given the hat, sash and gloves they were expected to wear. These garments might become part of their wardrobe, or, they could be sold for extra cash. Those who were required to provide their own garments were often seen to be wearing dingy shirts, thread-bare coats and time-worn hats. Men who picked up casual work as mutes might not be as diligent in their responsibilities, such as keeping silent and maintaining a mournful expression while they were on duty. These men also tended to have a fondness for liquor and it was quite common for them to go directly to the nearest tavern or public house after a funeral, which routinely caused comment about how by so doing they made a mockery of the solemnity of the funeral rites in which they had just participated.

audiophile

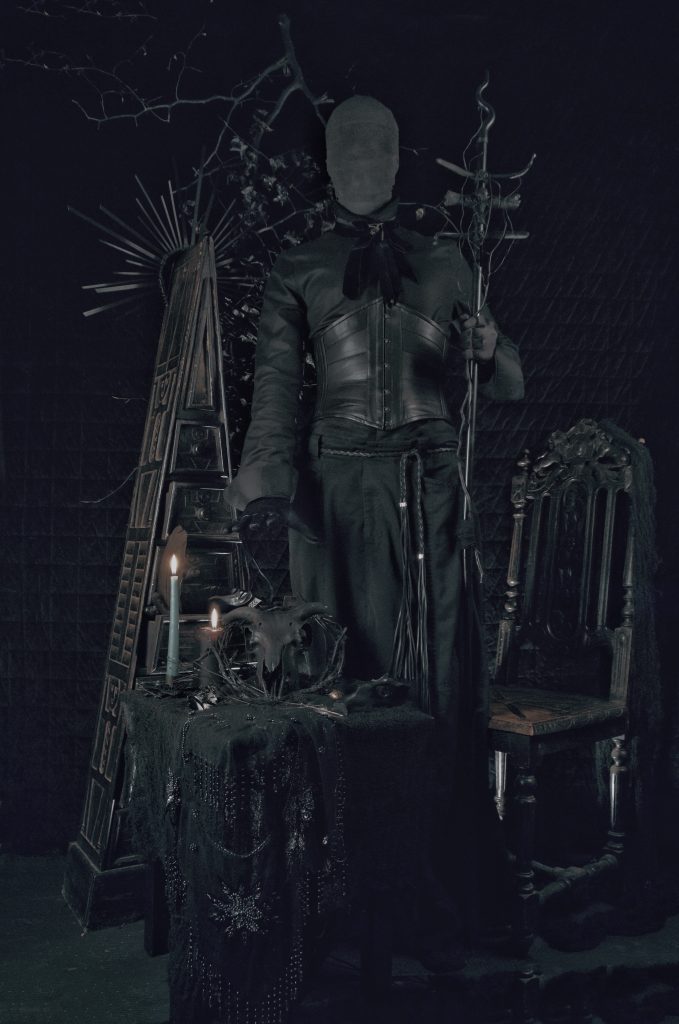

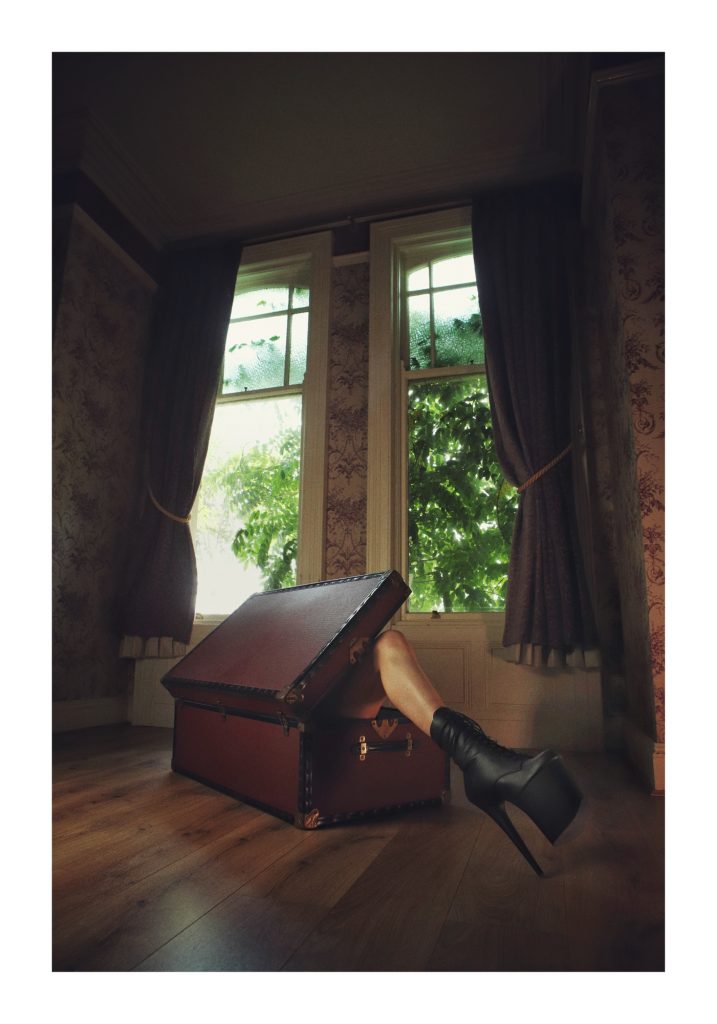

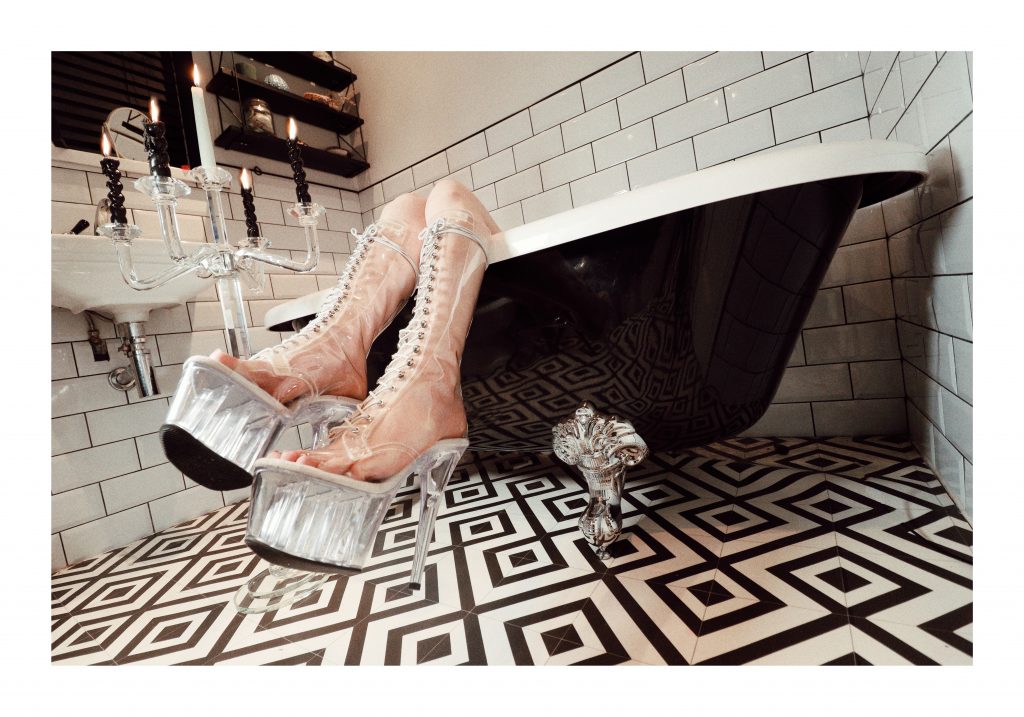

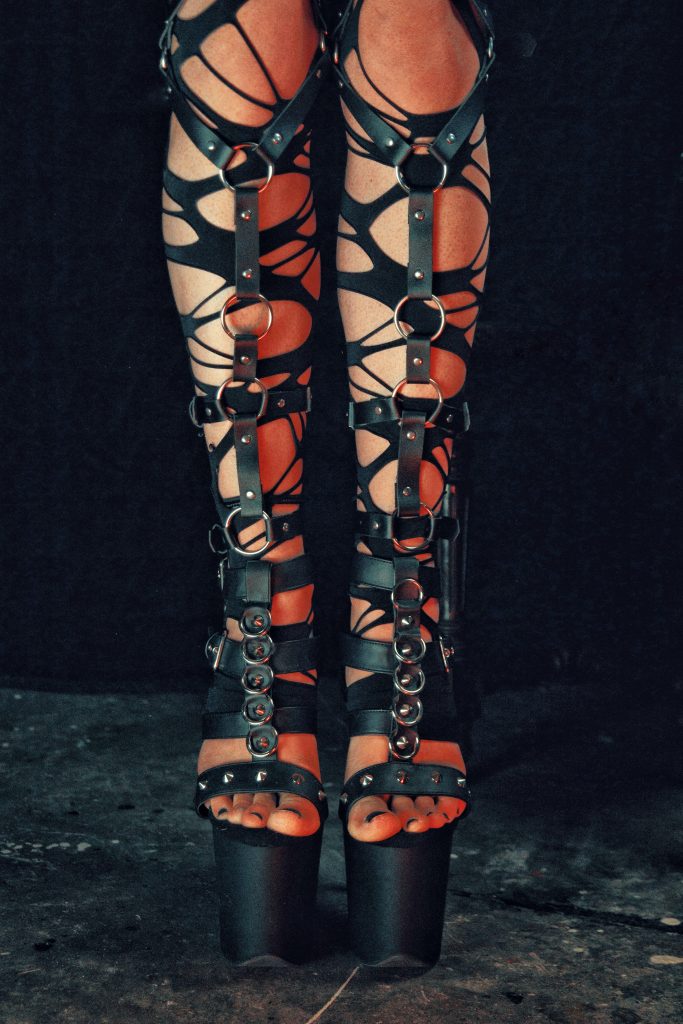

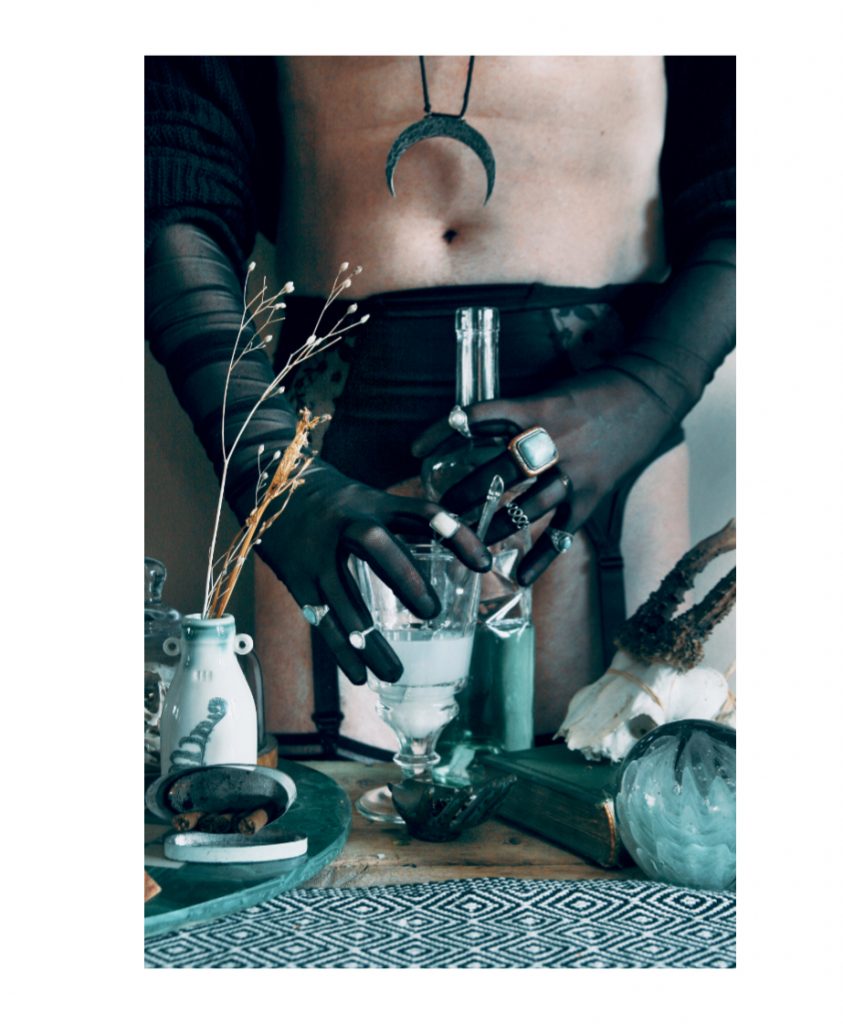

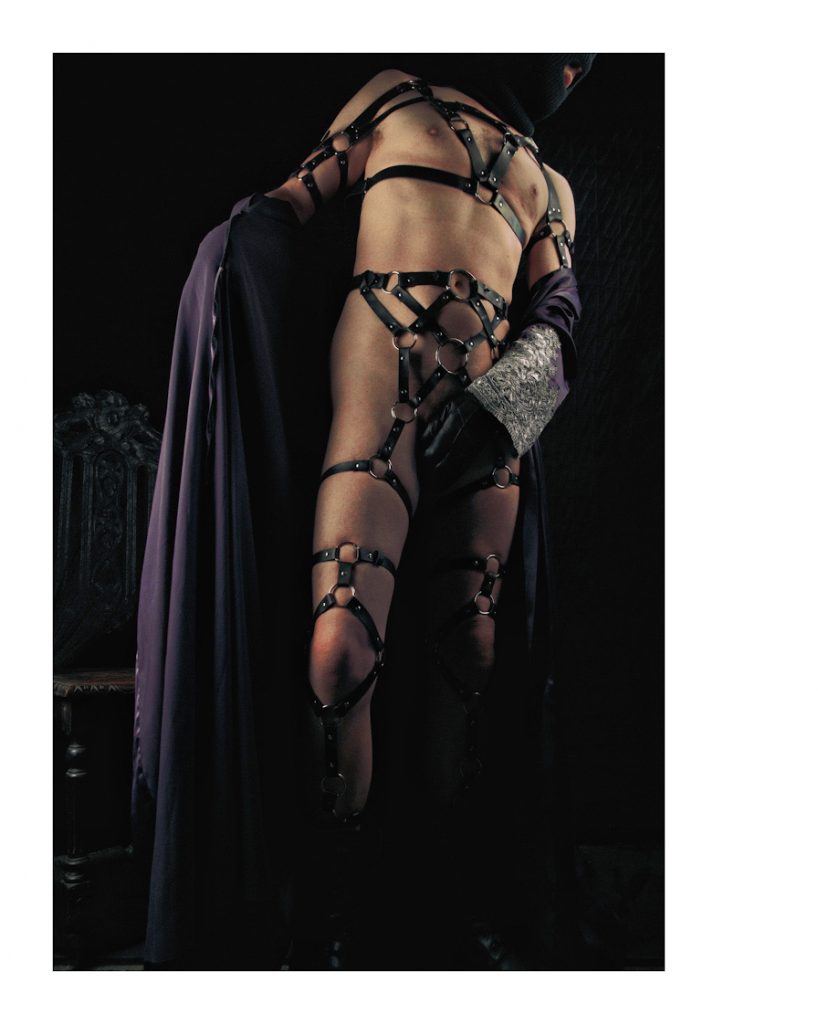

The dark mother prepares

stowaway

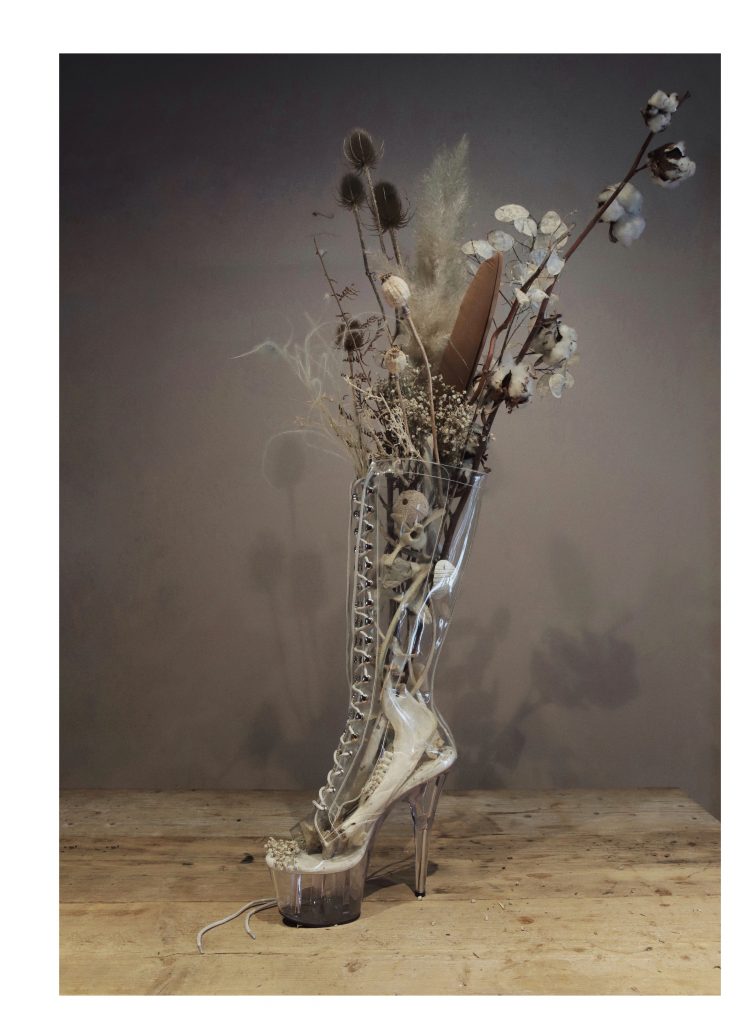

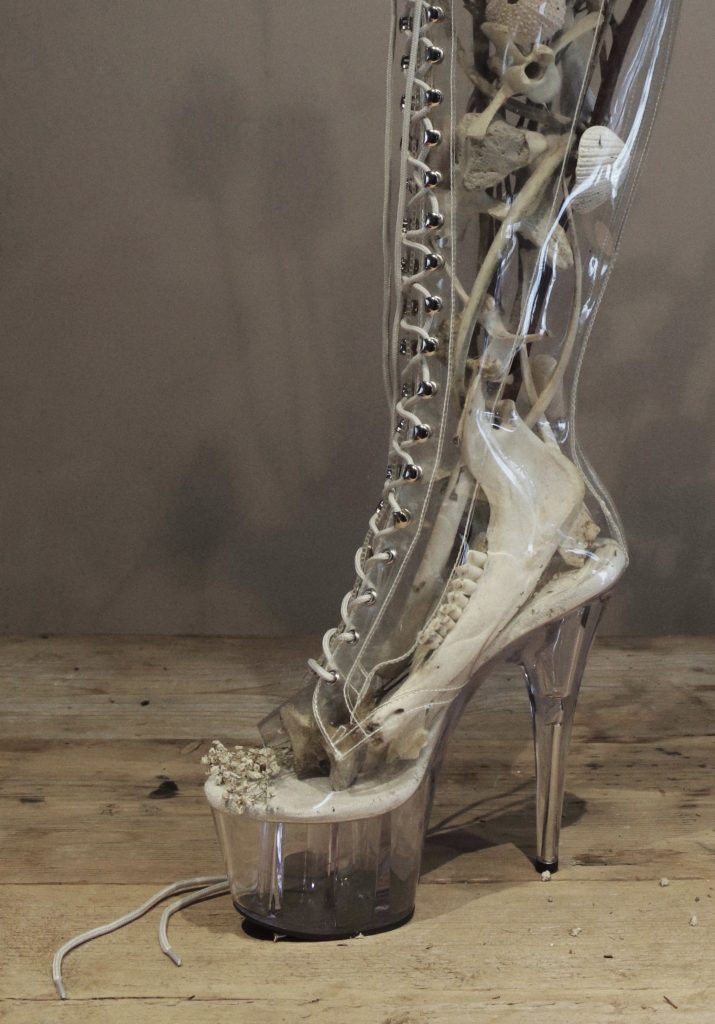

the preparation for the ritual, is the ritual…

The Absinthe Mythology — of the Green Fairy of liberation, of altered perceptions and unveiled meanings—appealed to creative libertines around the world. Vincent van Gogh was a convert, as was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Playwright Alfred Jarry sought his destruction in absinthe; Pablo Picasso dabbled in it for a time, painting The Absinthe Drinker and the cubist breakthrough The Glass of Absinthe, but never gave himself over to it.

Oscar Wilde declared, “A glass of absinthe is as poetical as anything in the world. What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset?” Even Ernest Hemingway, not especially known for decadence or dandyism, embraced absinthe.

He called it “opaque, bitter, tongue-numbing, brain-warming, stomach-warming, idea-changing liquid alchemy,” saying, “It’s supposed to rot your brain out, but I don’t believe it. It only changes the ideas.”

Hemingway succinctly captured the danger and allure of the pale-green drink. To enthusiasts it promised new ideas. To the unconverted it symbolized madness—“une correspondance pour Charenton,” a ticket to Charenton, the insane asylum outside Paris.

maybe if i stab myself deep enough you’ll crawl inside of me…